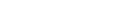

CJ's speech at Ceremonial Opening of Legal Year 2026 (with photos)

******************************************************************

Following is the full text of the speech delivered by Chief Justice Andrew Cheung, Chief Justice of the Court of Final Appeal, at the Ceremonial Opening of the Legal Year 2026 today (January 19):

Secretary for Justice, Chairman of the Bar, President of the Law Society, Fellow Judges, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen,

On behalf of the Hong Kong Judiciary, I extend a very warm welcome to all of you to the Ceremonial Opening of the Legal Year. This significant occasion serves as a timely reminder to our community of the vital role an independent judiciary plays in upholding justice and the rule of law. It also offers an opportunity to reaffirm the core values on which our legal and judicial institutions are founded.

The Judiciary's work over the course of 2025 is set out in detail in its Annual Report, published electronically today. In particular, I have provided an overview of the key areas of work undertaken during the past year in the Welcome Remarks. This allows me, in this year's speech, to devote attention first to some fundamental principles essential to the rule of law and judicial independence, which have been brought into focus by a recent case, before turning to another topic concerning the constitutional roles of the different branches of government in the protection of rights.

The long criminal trial of Mr Jimmy Lai and his companies before the Court of First Instance of the High Court has recently concluded, resulting in their convictions for national security and conspiracy offences. Sentencing remains pending, and appeals may or may not be forthcoming. As expected, the outcome of this high-profile trial has attracted significant international attention and commentary. Also as expected, given the prevailing geopolitical tensions, some of these responses have been critical not only of the prosecution and verdicts, but also of the courts and the rule of law in Hong Kong generally.

It is important to emphasise at the outset that the legal process remains ongoing. The defendants retain the rights to appeal. Any alleged errors, whether legal, procedural, or evidential, will be considered by the Court of Appeal, should an appeal be lodged. For obvious reasons, I will not comment on the merits of the case or make categorical assertions about the proceedings. The appropriate forum for resolving any such issues remains the judicial process itself. However, I would like to take this opportunity to highlight a number of general matters of importance.

To begin with, we fully respect the right of individuals to express their views. Few court decisions please everyone. Rather, the strength of our justice system lies in its adherence to the law and its openness to scrutiny. In this respect, it is no different from those in other developed common law jurisdictions. However, a comment or a criticism is only as meaningful as it is informed. Any serious comment or disagreement intended to be taken seriously must be grounded in a careful reading of the judgment and a sincere effort to understand the court's reasoning.

Hong Kong's Basic Law and general laws, along with the national security laws, all guarantee the independence and impartiality of the courts, and the right to a fair trial. They require that court decisions be based on the evidence and legal arguments presented, and not on extraneous considerations or public pressure.

These fundamental principles govern all criminal proceedings in Hong Kong. Save for narrow and well-defined exceptions, all criminal trials are conducted in open court, in accordance with established rules of criminal procedure and evidence. Members of the public, as well as the press, are permitted to attend hearings without undue restriction. Invariably, the prosecution bears the burden of proving the defendant's guilt beyond reasonable doubt. Both the prosecution and the defence are entitled to call witnesses, tender documentary and other forms of evidence, and make legal submissions. Unless they choose to represent themselves, all defendants are legally represented at trial, either by privately instructed lawyers or by those funded through the public purse. A defendant may, if they wish, give evidence in their own defence. If they choose not to do so, the prosecution may not comment on that fact, and certainly no adverse inference may be drawn from it to establish guilt. Unless the case is tried before a jury, all verdicts are accompanied by reasons. These typically explain the charges, summarise the prosecution's case and the defence, describe the evidence adduced, and set out the court's reasoning for its findings and conclusion. This transparent process, which is followed in all criminal trials with necessary adaptations where appropriate, ensures accountability and enables full and meaningful appellate review where required.

At the risk of stating the obvious, it should be noted that court decisions are subject to appeal or review in accordance with the applicable procedures. I have every confidence that the Court of Appeal and ultimately the Court of Final Appeal will, as always, act with integrity and professionalism in handling any appeals or reviews.

Under the Basic Law, the courts, as the judicial organ of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, are under a constitutional duty to hear and determine all cases that are properly brought before them. They concern themselves only with the law and the evidence, not with any underlying matters of politics, policies or other non-legal considerations. As professionals, our judges take seriously the Judicial Oath to administer justice fairly and impartially. Any suggestion that a judge would compromise their conscience or integrity for political or other extraneous considerations when hearing a case is, by its very nature, a serious one that should not be made without cogent evidence. Bald and unsubstantiated allegations of this kind merely indicate that the criticisms may themselves be influenced by political or other extraneous considerations.

As to sweeping comments on the state of the rule of law in Hong Kong arising from the outcome of a particular case, many of us may be forgiven for growing weary of simplistic assertions that the rule of law is dead whenever a court reaches a result one finds unpalatable. The rule of law in Hong Kong is far more robust and enduring than the outcome of any single case. It cannot be that the rule of law is alive one day, dead the next, and resurrected on the third, depending on whether the Government or another party happens to prevail in court on a particular day. Such a claim needs only to be stated to highlight how untenable it is.

As regards calls that are sometimes heard to halt proceedings or prematurely release a defendant, based on reasons such as occupation, background, or political causes, it should be emphasised that such demands not only circumvent the legal procedures established to ensure accountability under the law, but also strike at the very heart of the rule of law itself. A foundational tenet of the rule of law is that no one is above the law, regardless of their status, occupation, office, political affiliation, personal belief or conviction, popularity, wealth, connection, or any other characteristic. The law applies equally to all, without fear or favour. Those who are genuinely committed to upholding the rule of law must also be committed to allowing the courts to do their work according to established legal processes and without interference.

As to the threats of sanctions that have been made from time to time against our judges, it is clear that however these threats are framed, they are, in substance, attempts to interfere with judicial independence by means fundamentally at odds with the rule of law. Intimidation and threats are no different from bribery and corruption, they being, in truth, two sides of the same coin. Both are means of subverting justice, and have absolutely no place in a civilised society governed by the rule of law.

I would now turn to a different topic concerning the respective constitutional roles of the Judiciary, the Executive, and the Legislature in the protection of rights. It is, without doubt, an important aspect of any constitutional framework.

The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region is established by the Basic Law pursuant to Article 31 of the Constitution. In matters of fundamental rights, the Basic Law, along with the constitutionally entrenched Hong Kong Bill of Rights, provides a legal framework within which all public authorities must act.

I will first start with the courts. Their constitutional function is to adjudicate independently, applying legal principles to the facts before them and making reasoned decisions. In a constitutional or public law case, where it is alleged that the Government has breached or failed to protect a certain right, the court must carefully consider the claim by reference to the right asserted and any other related or competing rights or interests, the existing case law, the evidence adduced, and the justifications put forward in defence of the subject matter under challenge. If a case for breach is not made out, it is dismissed, usually with costs. If the case is established, the court must so hold and determine what remedies, if any, should be granted. In some instances, a legislative provision or administrative rule may be reinterpreted to eliminate the offending part, where possible. Where that proves infeasible, the court may have to strike down the provision or rule altogether, rendering it of no further legal effect. In other cases, the court may simply grant a declaration, that is, a formal court statement of the legal position concerning the rights, obligations or status of the parties, or other relevant matters. In all cases, the court's decision must be accompanied by clear reasons. Parties and stakeholders alike, as well as the public, are entitled to understand how the law has been interpreted and applied.

Courts exercise great care in granting legal remedies in constitutional and public law cases. Often, they leave room to the Government to determine, in accordance with the rule of law and principles of good governance, how best to fulfil its constitutional or public law duties. Judicial restraint in this context reflects constitutional discipline and a recognition of institutional limits. Courts administer justice by applying the law. They seek neither to govern nor to legislate. In fashioning remedies, courts strive to uphold both the substance of the rights at issue and the proper division of constitutional functions.

Before turning to the Executive, it is important to say something about the finality of judgments on the interpretation of a provision in the Basic Law or of a right guaranteed by it. When the Court of Final Appeal gives judgment on such a matter, its interpretation represents the authoritative statement of the law, subject only to any interpretation by the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress, and then only in prescribed and exceptional circumstances. The Court's interpretation binds all: the public, the Administration, and the Legislature, including individual members. This upholds the design of the Basic Law, which vests the power of final adjudication in the Court of Final Appeal. To say that an interpretation of the final Court is binding on all is simply to recognise what the Basic Law expressly provides regarding final adjudication. Respecting the Court's judgment is simply respecting the Basic Law.

People are, of course, entitled to hold different views on controversial matters. They may also express disagreement with a judgment. But disagreement with a final judicial interpretation does not provide a legal basis to depart from it. The constitutional space for debate lies not in reopening a judicially concluded matter, but in determining how best to conform our system to what is protected under the Basic Law as finally interpreted by the Court, taking into account all legitimate and relevant considerations.

The responsibility for compliance, and for taking remedial steps, ordinarily rests with the Executive. Naturally, most decisions that give rise to constitutional or public law challenges, whether concerning welfare, immigration, taxation, or public administration, are executive in nature. The Executive operates the policies and systems that govern our society. It is typically the respondent in judicial review proceedings. And it has both the duty and the capacity to bring its policies and systems into compliance. Depending on the facts, remedial measures may involve revising administrative policies and guidelines, modifying existing systems and procedures, re-allocation of resources, and, where primary legislation is required, introducing a bill supported by policy reasons and, where appropriate, public consultation. This duty flows directly from the rule of law and the constitutional imperative to uphold the Basic Law, including its protection of fundamental rights.

The Legislature, in turn, exercises a distinct and constitutionally protected role. Its members are elected to scrutinise, debate, and enact legislation. They do so under an oath to uphold the Basic Law. That oath establishes a constitutional framework but does not dictate how members must vote in relation to individual bills. Courts are careful not to intrude upon the legislative process, and fully respect the legislative discretion that the Legislature enjoys.

Some have sought to explain this judicial restraint by drawing comparisons with the United Kingdom, where Parliament is sovereign. It is, in many ways, a natural reference point, but not an equivalent model. In the United Kingdom, the constitution is largely unwritten, political in nature, and, crucially, Parliament is supreme. No court can strike down an Act of Parliament. No institution, including the judiciary, has the authority to dictate what Parliament must, or must not enact. The legal authority of Parliament is absolute, and its enactments are binding regardless of content.

Hong Kong's constitutional order is different. Our constitutional framework is written and legal in nature. All public authorities, including the Legislature, exercise their powers under the Basic Law, which itself derives from the Constitution. The Basic Law defines the scope and limits of institutional authority. Within that framework, the courts are tasked with interpreting and applying the Basic Law with finality. Subject to and within the legal parameters set by the Basic Law itself, it is for the Executive to propose legislation where required, and for the Legislative Council to consider and enact it as it deems appropriate. In this way, our system preserves both constitutional discipline and space for legislative discretion.

In practice, what emerges is a constitutional division of labour, with each branch of government operating within its constitutional role. Even on occasions when consensus between them proves elusive, at least for the time being, the system does not grind to a halt. The court's judgment stands as a vindication of the affected individuals' rights and triggers the Executive's duty of compliance under the law. As a result, incompatible administrative rules may fall away, and governmental policies and practices may evolve. New measures may emerge to alleviate the position. The resulting picture may not be perfect or seamless, but it reflects meaningful constitutional progress. And that, too, forms part of the constitutional model established under the Basic Law.

By definition, controversial matters attract divergent views. Public confidence in the rule of law need not be affected by the presence of differing perspectives on these matters between the branches of government. Far more important is the respect each shows to the other and their respective constitutional roles. With each branch maintaining its role and a robust respect for the rule of law, we believe that even complex, multi-dimensional issues can, in time, be worked through with both principle and practicality.

Last but by no means least, every one of us in the Judiciary shares in the deep sorrow felt throughout our community in the wake of the tragic fire that occurred in Wang Fuk Court in Tai Po last November. This horrific incident resulted in a devastating loss of life, inflicted great suffering on only too many families, and caused extensive damage to homes and property. As the community moves forward, our thoughts remain with those affected, as they work to recover and rebuild in the aftermath of this tragedy, supported by many across our society.

For its part, the Judiciary has announced measures to expedite and prioritise legal proceedings arising from the tragic fire. A task group led by the Chief Judge of the High Court has been established to oversee handling of cases across all court levels. In addition, a support team has been set up to manage probate matters and liaise with relevant departments. Probate-related fees for deceased victims will be waived, with other fee concessions to be considered on a case by case basis. The Judiciary will continue to draw on support from the legal profession, as appropriate.

It only remains for me to wish you and your families good health and a peaceful year ahead. Thank you.

Ends/Monday, January 19, 2026

Issued at HKT 18:10

Issued at HKT 18:10

NNNN